https://www.penguinrandomhouse.ca/books/566674/the-kitchen-by-john-ota/9780525609896

When a new book written by a friend or acquaintance comes into your hands, there’s always a moment of stress before you open the cover and dip into the pages. What if it’s unreadable? And, if it is bad, how will you tell them without being hurtful? The feeling is especially acute when the book isn’t part of a bigger body of work and you really don’t know what to expect. This was how I felt moments after I agreed to review John Ota’s The Kitchen for this newsletter. I was hoping for the best, but worried the book might only be about angles and ratios or other technical details an architectural writer might share between the covers of a book about historical kitchen design.

I met John Ota a couple of years ago in a tiny Orangeville coffee shop; he had driven from Toronto to attend my talk on a historical book I had written about the food served on an Edwardian cruise ship called the Titanic. Given my own fascination with culinary history and how analyzing what people ate in the past helps me to understand their lives, I knew I’d find things to like within the pages of a book about historic kitchens, and the good news is that The Kitchen is more than just readable; in fact, I think it has broad appeal.

The trick will be for booksellers to find the correct place to shelve it, because The Kitchen spans genres: it’s a memoir by a food lover; it’s a travelogue by a tourist with an eye for light and descriptive detail; it’s a love story brought to life by affectionate letters written home; and it’s an anthropological exploration of the ways cooking and feeding ourselves can reveal day-to-day life. Lastly, at least for this reviewer, The Kitchen is also a self-help book!

John may be predisposed to write a book that spans so many genres because of his training. His background is in architecture—he is an architectural writer and critic who specializes in preservation—a profession that I imagine requires one to be highly empathetic not only to the needs of a building’s current users, but also to the vision and intent of the original builder. John applies this emotional intelligence adeptly to create a highly readable book that uses sensory and descriptive detail to evoke the past.

Over the course of 13 kitchen visits, he charts the evolution of North American home cooking since the 17th century. He takes us from a stand-alone, discretely situated kitchen where servants created banquets for dignitaries using imported ingredients to an open-concept, luxurious cliffside monument to modern food enthusiasm where friends gather to relax, prepare local foods and eat before a spectacular mountain view.

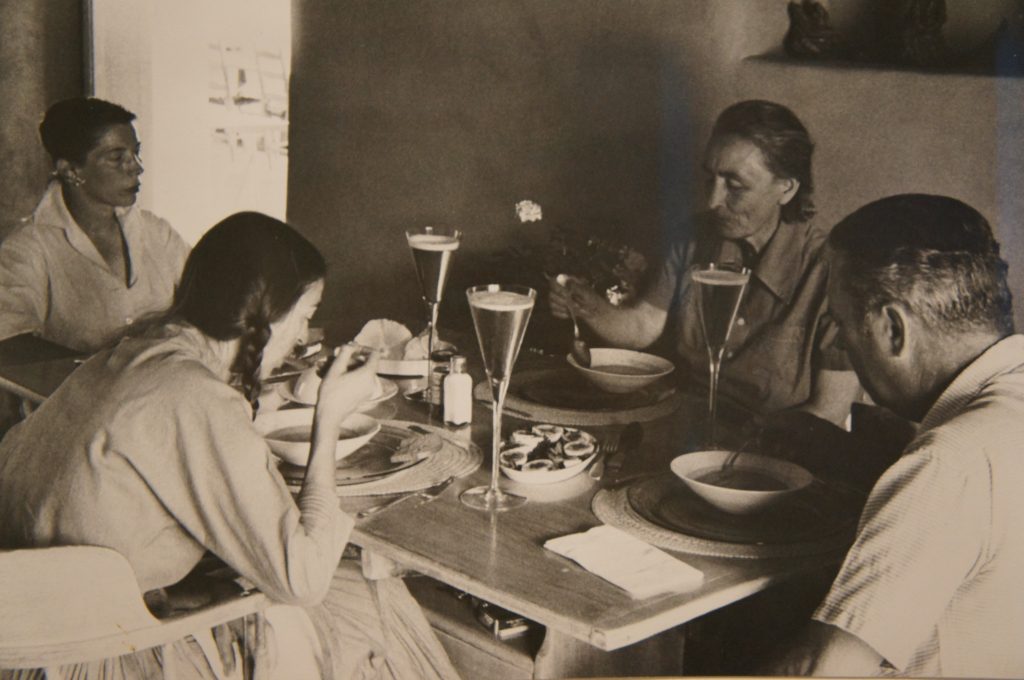

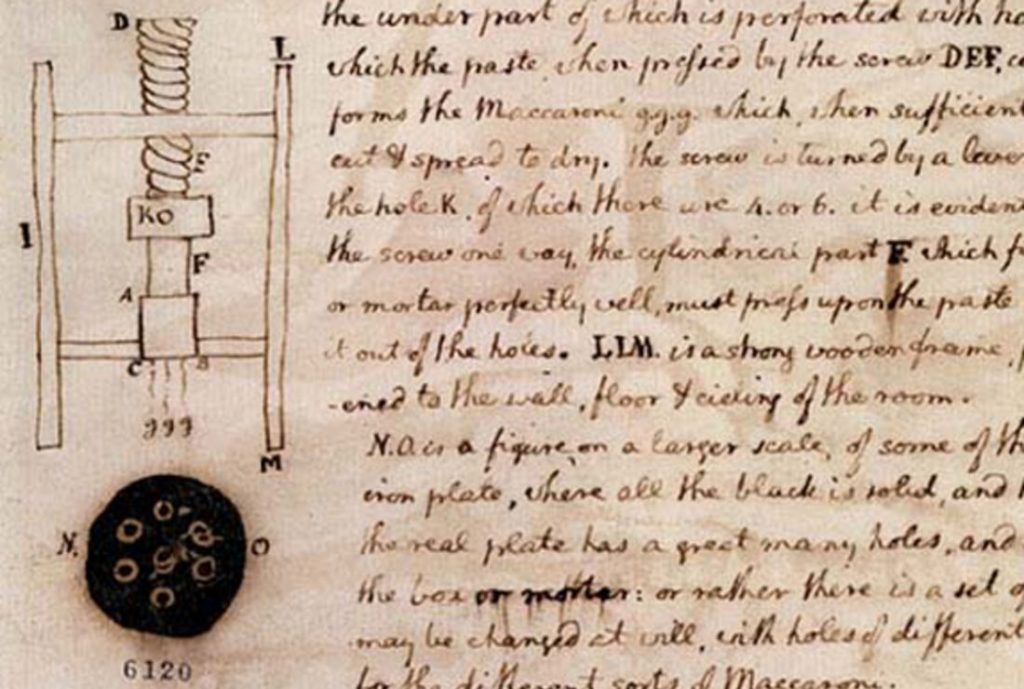

Along with the author, the reader visits kitchens created and used by historical icons (Julia Child, Georgia O’Keeffe and Thomas Jefferson, to name just three) as well as the cooking areas occupied by the everyday people whose names history has forgotten (such as Plymouth Plantation Pilgrims and Victorian tenement dwellers). He brings all of these people to life with descriptions of their homes, hearths and the foods they prepared to sustain themselves. In chapter one, John explicitly voices his mission: “I need(ed) to understand how the Pilgrims lived, what they ate, how they prepared their meals.” By the end of the chapter, he’s done exactly that.

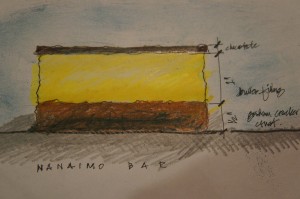

Every kitchen John visits is given a full chapter, each of which concludes with a letter home to his wife, Franny. In the introduction we learn that Franny, who has recently embraced cooking, hates their home kitchen and that John is visiting historic kitchens as part of the process of designing a cooking space that will please them both. His letters summarize what he’s learned at each location and how he’ll incorporate these lessons into the design of a space where he and Franny will find the creative inspiration to prepare wonderful meals and host celebrations.

It’s these short letters that elevate the book from a mere historical account to a useful and delightful narrative. In these notes, John reinforces the book’s utility as he distills each kitchen tour into lessons that reminded me that I should quit consulting magazines and social media for design ideas and start thinking of kitchens as places that personify their users and not their designers. For me, that insight has been transformative.

Midway through reading The Kitchen, I took an evaluating inventory of my own kitchen. As I stood there, the deficiencies I dwell on (such as having too many appliances cluttering my counters, or the fact that my stove top is so well worn that the numbers on the knobs are fading) became signifiers of a room that is well used by two passionate professional cooks.

Obviously, I’m no longer worried about what I’ll say when I next see author John Ota. In fact, I’m excited to see him, to say “Bravo!” And I am also excited to hear the details about the kitchen that he and Franny plan to create. Perhaps that project will be the basis for his next book? I do hope so.

Dana McCauley is a chef, food writer and food trend tracker. She is the author of the book, Last Dinner on the Titanic. @DanaMcCauley

This book review by Dana McCauley appeared in the April 2020 newsletter of the Culinary Historians of Canada http://www.culinaryhistorians.ca/wordpress/digest/book-reviews#thekit

The Kitchen: A Journey Through Time—and the Homes of Julia Child, Georgia O’Keeffe, Elvis Presley and Many Others—In Search of the Perfect Design by John Ota (Appetite by Random House, 2020).